what happens to us after lack of oxygen

Can you survive if you lot run out of air?

Scientific discipline tells us the human body tin can merely survive for a few minutes without oxygen. Simply some people are defying this accustomed truth.

* This story is featured in BBC Future's "Best of 2019" collection. Observe more of our picks.

There was a sickening crevice when the thick cable connecting Chris Lemons to the ship in a higher place him snapped. This vital umbilical string to the world to a higher place carried power, communications, heat and air to his diving suit 100m (328ft) below the surface of the sea.

While his colleagues call up the terrible noise of this lifeline breaking, Lemons himself heard zero. Ane moment he was jammed against the metal underwater structure they had been working on and then he was tumbling backwards towards the sea floor. His link to the send above was gone, along with any hope of finding his way back to it.

Nigh crucially, his air supply had likewise vanished, leaving him with just half dozen or vii minutes of emergency air supply. Over the adjacent 30 minutes at the lesser of the Northward Sea, Lemons would experience something that few people take lived to talk about: he ran out of air.

You might also like:

• What happens when the nutrient runs out?

• The real reason why sharks attack humans

• What life might be similar in alien oceans

"I'thou not sure I had a full handle on what was happening," recalls Lemons. "I hitting the sea bed on my back and was surrounded past an all-encompassing darkness. I knew I had a very small-scale amount of gas on my back and my chances of getting out of it were nigh not-existent. A kind of resignation came over me. I remember beingness taken over past grief in some means."

Chris Lemons had been saturation diving for about a twelvemonth and a one-half when the accident happened (Credit: Chris Lemons)

Lemons had been role of a saturation dive team fixing piping on an oil well manifold at the Huntington Oil Field, around 127miles (204km) east of Aberdeen on the e declension of Scotland. To do this work, divers must spend a calendar month living, sleeping and eating in peculiarly constructed chambers on board the swoop send, separated from the rest of the crew by a sheet of metal and glass. In these 6m-long tubes, the three divers acclimatise to the pressures they will feel once underwater.

Information technology is an unusual course of isolation. The three divers can talk to and meet their crewmates outside the chamber, merely they are otherwise cut off from them. The members of each team are entirely reliant upon one some other – information technology takes six days of decompression before they can leave this hyperbaric sleeping accommodation or help can get inside.

"Information technology is a very strange situation," says 39-twelvemonth-onetime Lemons. "You are living on the ship surrounded by lots of people who are but a sheath of metal abroad, only you are completely isolated from them.

"It is quicker to become back from the Moon than it is from the depths of the sea in some ways." (Read some of the oddest facts nigh the Apollo missions to the Moon.)

Decompression is necessary because nitrogen gas from the air divers breathe while underwater dissolves into their blood stream and tissues when they are at depth. As they come to the surface, the force per unit area of the surrounding h2o is lifted and the nitrogen bubbles out. If this happens likewise quickly, information technology tin can cause painful tissue and nerve impairment and even lead to decease if the bubbles form in the brain – a condition commonly known equally "the bends".

Divers who spend long periods in deep water need to decompress for several days in a hyperbaric chamber (Credit: Getty)

The divers who practice this work, all the same, take the risks in their stride. For Lemons, he was most concerned about spending such a long time abroad from his fiancée Morag Martin and the habitation they shared on the west coast of Scotland.

The day of xviii September 2012 had started usually enough for Lemons and the 2 colleagues he was diving with – Dave Youasa and Duncan Allcock. The three climbed into the diving bell, which would be lowered from the transport, the Bibby Topaz, to the sea bed where they would carry out their repair work.

"In many ways, it was only an ordinary twenty-four hours at the office," says Lemons. While not as experienced every bit the other two men, he had been a diver for 8 years and had been saturation diving for a twelvemonth and a half, taking part in nine deep-h2o dives. "The sea was a piffling rough on the surface, simply it was pretty clear underwater."

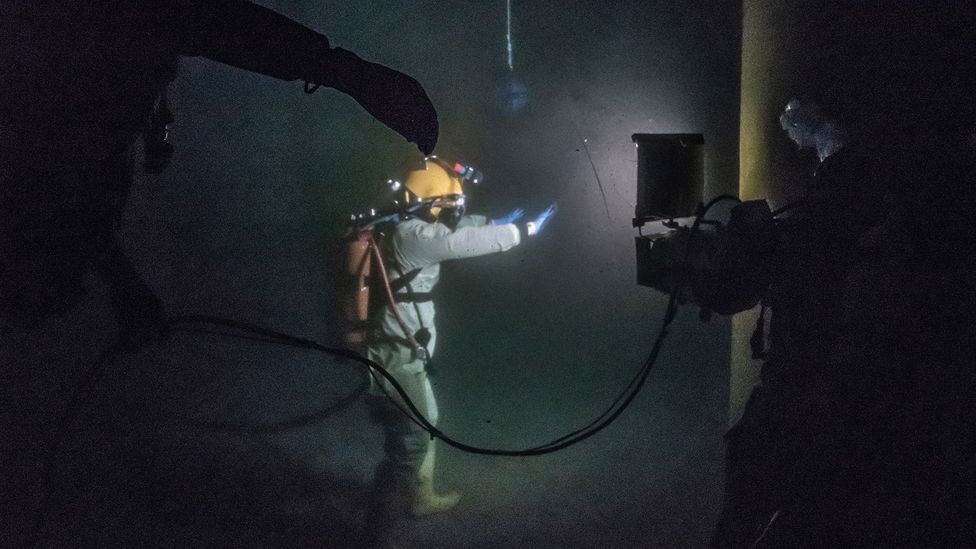

Chris Lemons spent 30 minutes on the body of water bed after the cable that was his lifeline to the ship above him snapped in rough seas (Credit: Dogwoof)

That rough sea, still, would trigger a chain of events that almost claimed Lemons's life. Normally swoop vessels utilize computer-controlled navigation and propulsion systems – known as dynamic positioning – to continue them over the dive site while they have people in the water.

As Lemons and Youasa began repairing the pipe underwater, with Allcock supervising them from the bell, the Bibby Topaz'south dynamic positioning system all of a sudden failed. The ship rapidly began globe-trotting off course.

On the sea floor, alarms sounded on the divers' communications system. Lemons and Youasa were instructed to become back to the bong. But as they began following their umbilical cords, the ship had already drifted back over the tall metal structure they had been working on, pregnant they had to climb over it.

When they neared the top, notwithstanding, Lemons's umbilical became snagged on a piece of metal sticking out of the structure. Earlier he could free it, the drifting transport pulled it tight, dragging him into the metal beams.

"Dave realised something was incorrect and turned to come back to me," says Lemons, whose story has been turned into a feature length documentary Last Jiff. "We had this strange moment where we were looking into each other'due south eyes. He was badly flailing to become to me, but the gunkhole was pulling him away. Before I knew it, I didn't have whatsoever gas because the cablevision was stretched so tight."

The crew on the ship watched helplessly from the surface as a remotely operated vehicle sent dorsum alive images of Lemons'due south fading movements 100m below (Credit: Floating Harbour)

The strain on the cablevision must have been immense. Composed of a tangle of hoses and electrical wires with a rope running through the middle, it creaked as the drifting boat pulled it tighter and tighter. Lemons instinctively turned the knob on his helmet to offset the flow of gas from the emergency tank on his back. Just earlier he could do annihilation else, the cable snapped, sending him tumbling back to the sea bed.

Miraculously, in the pitch darkness, Lemons managed to pull himself upright and feel his fashion back to the well structure, climbing information technology again to the meridian in the hope of seeing the bong and getting back to safety.

"When I got at that place, the bell was nowhere to exist seen," says Lemons. "I took a measured decision to calm down and conserve what little gas I had left. I only had near six to 7 minutes of emergency gas on my back. I didn't expect to be rescued, so I merely curled upwardly into a brawl."

Without oxygen, the human body tin only survive for a few minutes before the biological processes that power its cells brainstorm to fail. The electric signals that power the neurons in the encephalon decrease and eventually stop altogether.

"Loss of oxygen is correct at the very abrupt end of survival," says Mike Tipton, caput of the extreme environments laboratory at Portsmouth University in the UK. "The human trunk doesn't have a bang-up store of oxygen – perchance a couple of litres. How you use that upwardly depends on your metabolic rate."

The human torso should just be able to survive for a few minutes without oxygen at residual and less if stressed or exercising (Credit: Dogwoof)

Dorsum on board the Bibby Topaz, the crew desperately tried to manually navigate back into position to salve their lost colleague. As they drifted further away, they launched a remote-controlled submarine in the promise of finding him.

When it did, they watched helplessly on its cameras as Lemons's movements gradually stopped, his life fading away.

"I can recall pulling the last bits of air from the tank on my back," says Lemons. "It takes more endeavor to suck the gas down. It felt a fleck similar the moments before yous fall asleep. It wasn't unpleasant, merely I can retrieve feeling angry and apologising a lot to my fiancée Morag. I was aroused about the damage this was going to do to other people. So in that location was nothing." (Learn what it would be similar if we all knew when we might die.)

The common cold h2o and extra oxygen that had dissolved in Lemons's blood while he was working helped him to survive for and then long without air (Credit: Dogwoof)

It took around 30 minutes before the crew of the Bibby Topaz were able to regain control and restart the failed dynamic positioning system. When Youasa reached Lemons on summit of the underwater structure, his body was withal.

Through sheer volition, Youasa dragged his fallen colleague back to the bell and passed him upwards to Allcock. When they removed his helmet, Lemons was bluish and not breathing. Instinctively, Allcock gave him 2 breaths of mouth to mouth resuscitation.

Miraculously, Lemons gasped back into consciousness.

"I felt very groggy and there were some flashing lights, simply I don't accept many lucid memories of waking up," says Lemons. "I remember Dave sitting crumbled on the other side of the bell looking wearied and not really knowing why. It was only a few days afterwards that I realised the gravity of the situation."

Nearly vii years later, Lemons is notwithstanding perplexed as to how he managed to survive for so long without oxygen. Common sense suggests he should have perished after then long at the bottom of the sea.

Just it seems likely the cold water of the North Sea may have played a role –around 100m (328ft) down, the water was probably beneath 3C (37F). Without the hot water flowing through the umbilical cord to heat his suit, his torso and brain will have apace cooled.

A sudden loss of pressure level on an shipping tin leave passengers struggling to breathe in the sparse air which is why oxygen masks are provided (Credit: Alamy)

"Rapid cooling of the brain tin increase survival time without oxygen," says Tipton. "If you reduce the temperature by x degrees the metabolic charge per unit drops by a half to a third. If you lower the brain temperature downward to 30C (86F), it can increase the survival time from 10 to 20 minutes. If y'all cool the brain to 20C (68F), you can become an hour."

The pressurised gas that saturation divers usually breathe may accept given Lemons an additional chance. When animate high levels of oxygen nether pressure, it tin deliquesce into the claret stream, giving the trunk additional reserves to depict on.

Going hypoxic

Divers are perhaps the most probable people to experience a sudden loss of their air supply. But there are many other situations where the oxygen supply can be cut off. Firefighters often rely on animate equipment when entering smoke-high-strung buildings, while high-altitude fighter jet pilots too use breathing masks.

At the less extreme end, a lack of oxygen – known as hypoxia – tin can affect many other people. Mountain climbers feel low levels of oxygen when they are on high mountains, a status which often has been blamed for accidents. When levels of oxygen drop, brain function can endure, leading to poor decisions and confusion.

Chris Lemons's extraordinary story of survival has been turned into a feature length documentary called Terminal Breath (Credit: Dogwoof)

Patients undergoing surgery will also often undergo balmy hypoxia, which is idea to impact their recovery. Strokes are too caused by a patient'south brain being starved of oxygen, leading to cell death and damage that tin can take lasting furnishings on their lives.

"At that place are a lot of diseases where the concluding stage is hypoxia," says Tipton. "I of the things that happens is that people who are hypoxic beginning to lose their peripheral vision and they end up looking at a point. It is thought to be the reason why people report seeing a light at the stop of the tunnel in well-nigh decease experiences."

Lemons himself survived his fourth dimension without oxygen unscathed. He found only a couple of bruises on his legs after his ordeal.

But his survival is not unheard of either. Tipton has examined 43 divide cases in the medical literature of people who have been submerged in water for long periods. Iv of these recovered, including a two-and-a-one-half-year-old daughter who survived beingness under water for at to the lowest degree 66 minutes.

"Children and women are more likely to survive because they are smaller and their bodies tend to cool much faster," says Tipton.

Mountaineers on the world's highest mountains, such as Everest, demand to use supplimentary oxygen supplies due to the thin air (Credit: Alamy)

The training of saturation defined like Lemons may as well be inadvertently teaching their bodies to cope with extreme situations. Researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in Trondheim have institute that saturation divers suit to the extreme environment they work in by altering the genetic activity of their blood cells.

"We saw a marked change in the genetic programs for oxygen transport," says Ingrid Eftedal, head of the barophysiology inquiry group at NTNU. Oxygen is carried around our bodies in haemoglobin, a molecule constitute in our red claret cells. "We plant the activity of genes at all levels of oxygen transport – from haemoglobin to the production and activity of crimson claret cells is turned down during saturation diving," Eftedal adds.

Since the blow, saturation divers now carry supplies of emergency air that can concluding twoscore minutes rather than 6 or vii (Credit: Dogwoof)

She and her colleagues believe this might be a response to the high concentrations of oxygen they breathe while underwater. It is possible that the slow-downward of oxygen transport in Lemons's trunk allowed information technology to brand the meagre supplies information technology had terminal longer.

Exercising earlier diving has likewise been shown to help reduce the chance of developing the bends.

Studies of indigenous people who habitually free dive without additional air have also shown just how much the human trunk can accommodate to life without oxygen. The Bajau people in Indonesia can attain depths of upwardly to 70m (230ft) while holding their breath equally they hunt for food with spears.

Lemons says he remembers zippo from the moment he took his terminal breath to when he regained conciousness, bewildered, on board the diving bell (Credit: Floating Harbour)

The spleen is idea to play a cardinal role in enabling humans to gratuitous swoop.

"There is something called the mammalian dive reflex, which in humans is triggered by the combination of holding your breath and submerging yourself in water," says Ilardo. "I of the effects of the swoop reflex is contraction of the spleen. The spleen acts as a reservoir for oxygen-rich red blood cells, and when it contracts these red blood cells are pushed into apportionment, providing an oxygen heave. It tin can be thought of as a biological scuba tank."

Traditional costless divers of the Bajau people in Republic of indonesia have evolved enlarged spleens to help them spend longer underwater (Credit: Alamy)

With larger spleens, it is thought the Bajau benefit from a greater injection of oxygenated blood and so tin hold their breath for longer. One Bajau diver that Ilardo met told her he had spent thirteen minutes underwater.

Lemons himself returned to diving about iii weeks afterward his blow – at the very spot where information technology had happened, to finish the task they had started. He has besides married Morag and they have a daughter together.

Reflecting on his brush with death and his miraculous survival, he doesn't take much credit for his ain deportment.

"One of the greatest reasons I survived was the quality of the people around me," he says. "In truth, I did very lilliputian. Information technology was the professionalism and the heroics of the ii in the h2o with me and everyone on the ship. I was very lucky."

Every bit he ran out of air, Lemons's main thoughts were of his fiancée Morag, who he promptly married later on the accident (Credit: Chris Lemons)

His accident has triggered a number of changes in the diving community. They now use emergency tanks that conduct 40 minutes of air rather than 5. The umbilical cords are at present festooned with fairy lights so they can be seen more than easily under water.

The changes in his ain life accept non been then dramatic.

"I've even so got to change the nappies," he jokes. But he does notice himself thinking about death differently. "I don't see it as something to be feared whatever more than. It is more about what yous exit behind."

* Last Jiff will be shown on BBC Scotland on 7 May at 10pm and will be available in the UK online.

Worst Case Scenario

This article is part of a new BBC Time to come column chosen Worst Case Scenario, which looks at the extremes of the human experience and the remarkable resilience people display in the face of adversity.

It aims to expect at ways people take coped when the worst happens and what lessons we can learn from their experiences.

--

Join 900,000+ Futurity fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow usa on Twitter or Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called "If You Just Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked choice of stories from BBC Future, Civilization, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Fri.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190423-the-man-who-ran-out-of-air-at-the-bottom-of-the-ocean

0 Response to "what happens to us after lack of oxygen"

Postar um comentário